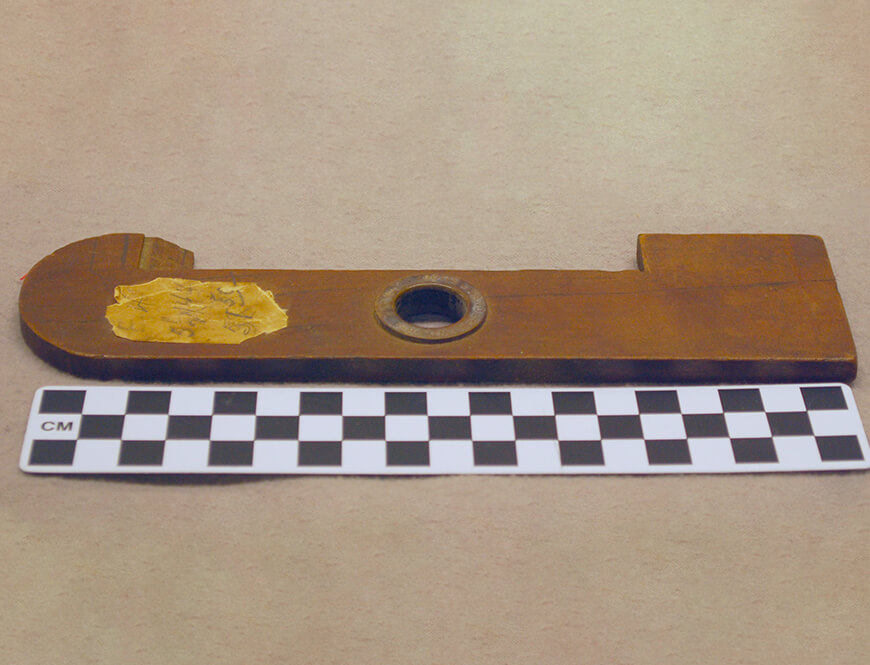

This item is a device for measuring cigars, called a cepo in Spanish. This device has a notch that would measure length, and a ring though the middle of it that measures a cigar’s diameter, referred to as the ring gauge. The ring gauge in cigars measures the thickness of the cigar to a 64th of an inch. The ring through the center of this object is 44/64 of an inch in diameter, which translates to a 44 ring gauge.

This gauge was donated by Bill Finck Sr., of Finck Cigars. The Finck family has been making cigars in San Antonio since 1893, when Mr. Finck’s grandfather started the company. During that time, there were a lot of cigar makers in Texas, especially in German communities. Henry William Finck moved to the San Antonio area from New Orleans, after his doctors urged him to seek a drier climate to help treat an illness he was suffering from, thought at the time to have been tuberculous. Henry had learned how to make cigars in New Orleans while working for cigar manufactures there, he only formed his own cigar company after moving to San Antonio.

During the late 19th century, cigars were more popular than cigarettes and most major cities in Texas had cigar manufacturers. There were cigar companies in San Antonio, Seguin, Round Top, El Paso, Shiner and Fredricksburg to name a few. Most of these companies have since shut down, and Finck’s is one of the few that remain. Perhaps it is the long-running association between Finck’s Cigars, and the now-closed Travis Club that is responsible for Finck’s long-term success. During World War I, the Travis Club opened its doors to the military officers to gather and relax while on leave. As a result, the Travis Club’s private label cigars, made exclusively by Finck’s for the club members, were in high demand by the soldiers. To this day, Finck’s Cigar Company continues to support the military and military veterans through various fundraisers.

From the late 19th through early 20th century, there were a number of inventions made to help speed up the process of making cigars. Gauges like this one, at the UTSA Institute of Texan Cultures, helped to ensure each cigar was made to the same standard length and diameter. This cigar gauge was patented by John J. Sander of New York, in 1884. Mr. Sander was known to have been in business with his father-in-law George P. Bruck. He he lived in Brooklyn, having arrived there in about 1880 with his parents who had emigrated here from Germany in 1874.

Most Finck Company cigars are made by hand, from start to finish. In the late 1800s when boxes started becoming a standard way of selling cigars, maintaining a uniform length became an important manufacturing issue. This gauge is one way to have a simple method of quality control for both the gauge of the cigar and the length. The finished cigar is placed in the wide gap at the top, to measure the cigar length. It is also passed through the ring in the center to verify the ring gauge. Finck’s no longer uses this type of gauge to measure cigars, instead they use a device with multiple size gauges so that one device can measure any type of cigar.

Cigar rollers, like many of the manufacturing workers in San Antonio during the Great Depression, were paid by the piece, rather than by the hour. This type of pay, called piecework, was meant to encourage workers to produce large numbers of items. At the Finck Cigar Company, workers were expected to use a set amount of tobacco to roll 500 cigars. Employees were penalized for each cigar that did not meet the size or quality standards, by having to roll extra “penalty cigars.” These extra cigars did not count toward the number of cigars made, and so the worker’s were not paid for any “penalty cigars” made. The number of penalty cigars, combined with pressures to unionize, led to several strikes in the 1930s. Several other industries such as the garment workers, pecan shellers, and launderers faced strikes in the 1930s over working conditions. At this time there was also an increased movement for unity among Mexican-American laborers, spearheaded by leading women in the community such as Emma Tenayuca and Manuela Solis Sager.

Needless to say, working conditions in San Antonio (and across the country) have undergone considerable reforms since then for safety, work hour limits, better pay, and protection against discrimination. These reforms came about for a number of reasons, including: mechanization of labor, increased numbers of women entering the workforce during World War II, as well as the workers’ and civil rights movements of the 20th century.